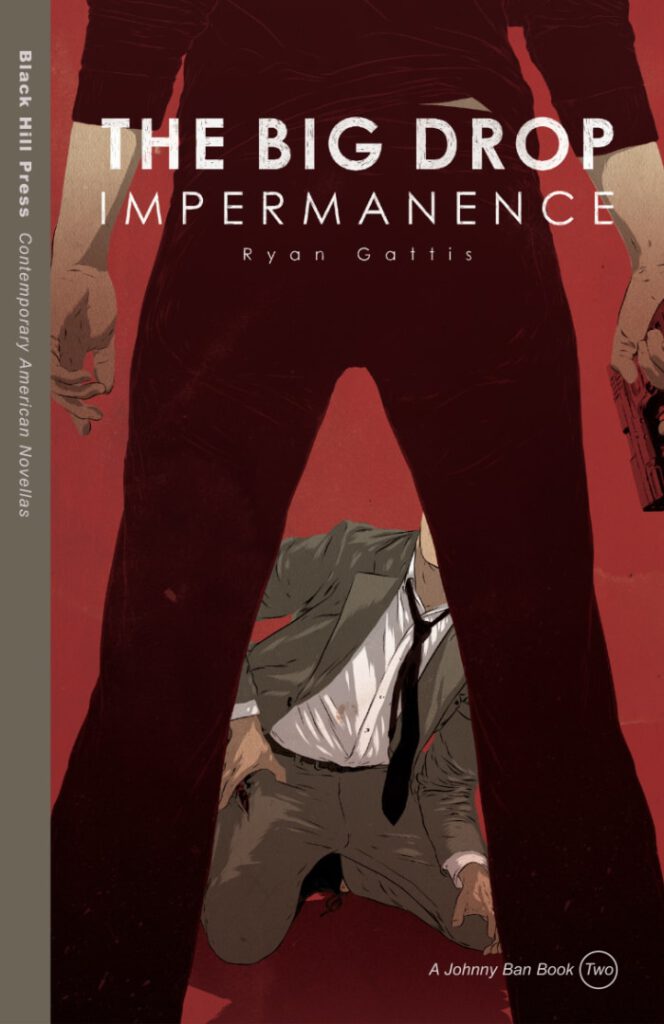

The Big Drop (Part 2)

Synopsis

After killing a yakuza in self-defense, an ex-military translator owes a debt that is payable only one way: take the dead man’s place searching for a missing woman in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. Fusing gritty yakuza action with elements of classic noir in the city that started it all, the novella smashes Johnny Ban into a rarely explored corner of Los Angeles, sending him in search of two distinct parts of his past: his long-buried Americanness, and his first love—a Japanese woman up to her neck in trouble.

Publisher's Note

“The Big Drop tracks Johnny Ban, ex-military translator and barely-was pro boxer, on a yakuza-prompted mission to find the missing love of his life. This 2-part noir serial begins with Homecoming and ends with Impermanence. It’s the simplest combination in boxing: the 1-2. When the quick first punch lands, it obscures the opponent’s vision long enough for the power shot to find a home and do maximum damage—because the best punch is, and always will be, the one you never see coming.”

The Story Behind the Books

Both of The Big Drop books are, I suppose, a love letter to Little Tokyo—a Los Angeles neighborhood not far from where I was living in Downtown at the time. I’d been spending time there on & off ever since I had interned in the Japanese American National Museum while at university in 2000. When I moved nearby many years later, I visited often because it was the part of the city where I felt most at home. Every Sunday I went to the Nishi Hongwanji Temple. This was where I met a Japanese American gentleman by the name of Ken. He was Nisei. Second-generation. His parents came from Japan.

When Ken heard I was a writer, he didn’t speak to me for two weeks. After that time, however, he announced his opinion to the entire congregation in a too-loud voice, “I read Kung Fu High School. It was one of the worst books I ever read!”

That shocked me, and I was definitely embarrassed, but rather than get angry, I asked him why he thought so. He had a litany of reasons, many of them good, so I asked him to lunch in order for us to speak further. It was while at one of his favorite noodle places that I told him I was working on a new book about a Japanese ex-serviceman who was part of the first unit to step foot on foreign soil since World War II.

He wondered aloud why I was interested in that. I told him I was from a military family and that I had a friend in the Army Air Corps who flew helicopters. In his short term of service, he did a tour in Afghanistan & 14 months in Iraq. When he got back from serving, he’d call any hour of the day or night and need someone to sit with him & talk. So I did. This went on for nearly two years, gradually waning in frequency, as he acclimated to life outside a war zone. I was proud to be there for him, but it wasn’t without its price.

“These were some of the most powerful talks I’d ever had with anyone, but,” I admitted to Ken, “I didn’t talk much. I mostly just listened. And sometimes what I’ve heard just weighs on me.”

I wanted to create a character, and a story, to deal with those listening sessions. I had to get it out somehow, and to write some modern-day L.A. noir seemed like just the right frame to give me some distance from it.

After lunch, Ken told me he’d read whatever it was I’d been writing, and that he’d help it not be terrible. I thanked him for that. The next Sunday, I brought a manuscript. Ken read every word, and even provided notes & a generous copyedits in red pen that looked like spiders had dipped their legs in blood and run over every page. He told me never to thank him for the guidance he gave me, but I suppose this is me doing just that. The Big Drop simply wouldn’t be as good without his insight.